Concepts in Programming Languages, Part I: Judgements and Inference Rules

From a layman's perspective, the field of programming language research is full of jargon, greek letters, and weird symbols. On the one hand, Those common parlances make the programming language papers concise. On the other hand, you need not only mathematical maturity but also domain knowledge to understand them.

Since I am taking a Fundamentals of Programming Languages course, I want to share the key concepts I learned in a series of blog posts. And I hope to write them in a "mortal-understandable" way to unravel the mysterious field of programming languages.

I want to thank Professor Chang for offering this fantastic course, and my classmates for creating a vibrant discussion environment. I also need to make a disclaimer that many ideas of those posts come from the classroom. I would cite writing texts when apply, but it is impossible to cite in class discussions. Of course, all errors are my own, and please contact me for anything wrong.

A lot of the mathematical concepts in the programming language field comes from the branch of propositional logic. Thus, this first post focuses on the formal language of Judgements, and Inference Rules.

Judgements

A judgment is a statement or an assertion on a given abstract syntax tree. Below are some standard notations we use for the judgments 1:

Notice in the above examples such as , is an unknown variable. We call those judgement forms And we can plug in actual values into the variables of judgement forms to get a judgement:

As we can see, judgments can either be true or false.

You can consider it is a function application that returns a bool.

Inference Rules

Inference rules are a logic form that takes premises and returns conclusions. They generally have the standard form of the following:

You can read them as "if all the premises are satisfied, then the conclusion."

Let's inductively define the natural numbers by the inference rules.

In this inference rule, we state that a natural number is either zero or a succession of another natural number. A rule without any premise, such as the first one, is called an axiom.

Because using inference rule to describe syntax is verbose, a common way to describe syntax is by grammar notation like the Backus normal form (BNF). A grammar of a programming language is a set of inductively defined terms. For example, for natural numbers, we can describe them as

However, inference rules can express much more than syntax. For example, let's define the semantics of the operator of the natural number:

We can define more operations, such as and , by the inference rule. Let's look at another example, a singly linked-list of natural numbers:

This grammar means that a is either or a -cell of natural number and another . A is an empty list, and a is a "node" of the singly linked-list that contains an individual element and points to a sub-list.

Now we can start to define operations on with inference rules.

For example, we can define a head function that gets the first element of the list:

Partial Function, Total Function, and Error handling

Notice our version of head is a partial function,

which means not all the list has a mapping to a natural number through head.

In this particular case, we have not defined the meaning of head(Nil).

We have several choices of dealing with such partial functions,

one is to leave the operation as undefined.

This approach is what the C programming language takes, and it is the best for optimization,

though it impairs the type safety.

Another approach is to make such a function call "error" or "exception" such as

And a third approach is to transform this operation to a total function:

A lot of the modern programming language becomes eclectic on error-handling strategies.

For example, the Rust programming language offers all three approaches in different contexts.

For certain operations, it not only offers a default "safe" version either with the second approach (panic) or the third approach (Option and Result),

but also an "unsafe" version with the first approach.

Derivation

You can easily create nonsense such as , so how to prove a judgment is correct? To prove a judgment, you write derivation (also called derivation tree or proof tree).

A derivation always starts from axioms and ends at the judgment we want to prove. For each step, we apply an inference rule to the previous judgment (s).

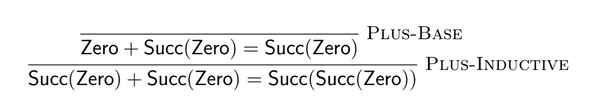

For example, to prove "1 + 1 = 2" with our definition of nat, we have

Reading from bottom to top, you can find that the derivation is analogous of the execution of a program:

Succ(Zero) + Succ(Zero)

= Zero + Succ(Succ(Zero))

= Succ(Succ(Zero))We can trace the execution of the + operation by substitution easily because it is a pure function.

In other words, + is deterministic and side-effect free, at least at the level that we concern.

Analogy to programming

All of the mathematical notations that we talked about have programming counterparts. Below is a table comparison between math notation and programming:

| Mathematical Notation | Implementation |

|---|---|

| Judgement form | A function signature of a function that returns bool |

| Judgement | Function application |

| Inference Rules | Function body |

| Derivation | Evaluation/Execution |

Let's say that we have the judgement form , we can write it as a function signature

val head : (l: nat list, e: option(nat)) -> boolThe inference rule of head can be view as the function body.

let head (l : nat list, e: option(nat)) =

match l with

| [] -> false

| hd::_ -> hd = eAnd the judgement such as is analogous to function application such as

head Cons(Succ(Zero), Nil) Succ(Zero) (*true*)I use OCaml syntax as an example, but it applies to any programming languages.

The advantage of an ML-family language such as OCaml in my use case is there excellent support for inductively defined types such as nat and list.

Notice that the literal translation from math generates very inefficient implementations.

In an actual implementation, You would probably write the head function as:

let head (l : nat list) =

match l with

| [] -> None

| hd::_ -> Some(hd)Nevertheless, it is still useful conceptually to see the connection between the mathematical notation and the actual programming.

"Type error" in judgements

It is easy to make "type error" when writing judgments and inference rules.

For example, the following inference rule is incorrect as + is not a natural number, so we cannot put it inside a Succ.

It is equally easy to make this kind of mistake when coding a tree-walking interpreter by mixing the abstract syntax and the values. If you are using a statically-typed language, the type-checker will catch those kinds of errors. On the contrary, when writing judgment and inference rules, you are on your own, so building a mental "type checker" helps tremendously in writing judgments correctly.

Summary

Judgments and inference rules are the fundamental building block of the formal definition of programming languages, and it is hard to find a programming language paper without them. Thus, it is crucial to understand how to read and write in such notations.

- Robert Harper. Practical Foundations for Programming Languages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, Second edition, 2016.↩